I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert…Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

We got to the Ramesseum a little before sunset and there was something about the quality of the light and the shapes of what’s left of the temple that meant I could see why it would inspire poetry. In looking up the temple (and checking the words of the poem) to write this post I discovered that Ozymandias wasn’t just a name Shelley invented, it’s a Greek rendering of User-Ma’at-Ra (which is one of Ramesses II’s names). And the inscription wasn’t invented out of whole cloth by Shelley either – in the 1st Century AD Diodorus Siculus visited the site and (erroneously) claimed to have seen an inscription on the statue: “I am Ozymandias, king of kings, if any would know how great I am, and where I lie, let him excel me in any of my works.”

As always, my photos from this site are on flickr. Click here for the full set or on any image (other than the plan) in this post to go flickr.

The inscription might be an invention but I rather suspect Ramesses II would like it. The Ramesseum is his mortuary temple, the Egyptian name of which means “The Temple of Millions of Years of User-Ma’at-Ra United with Thebes in the Estates of Amen West of Thebes”. The overall layout of the temple is much the same as Seti I’s mortuary temple or Medinet Habu (Ramesses III’s mortuary temple) both of which we visited later in the trip. Although the plan above marks in all the walls etc it’s a lot more ruined than that appears.

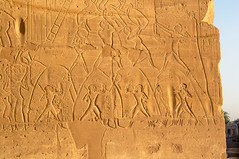

We approached the temple from the north side (right hand side of the plan), walking down a long walkway past a reconstructed large statue of Anubis. This would once have been part of an avenue lined with these statues (similar to the Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak & Luxor temples) – I wish more of them survived, that would be quite a sight to see! We entered the temple into the first court between the First Pylon and the Second Pylon – you can’t get to the front of the First Pylon these days as there is a village up next to it, and the gateway is blocked up. The pylon is in a pretty poor state but on what’s left of the side we could see you can still see the reliefs. As always with Ramesses II these focus on the Battle of Kadesh, his favourite piece of propaganda. The lefthand wall of the pylon has the King seated on a throne, meeting with his advisers, while all around his army are encamped. On the right hand wall are chaotic scenes of the battle itself.

Turning around to look at the Second Pylon what one mostly looks at is the colossal statue that inspired Shelley’s poem. It’s not known if it was one of a pair, and may originally have been intended for Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple (and then usurped by Ramesses II). According to the Kent Weeks Luxor guide, it is the largest monolithic statue ever sculpted. The ear is over a metre long, and the shoulders are over 7m broad. It’s not known when it fell – but it was sometime between when Diodorus Siculus visited and the 18th Century AD.

Beyond the Second Pylon is the Second Court, which is mostly in ruins. There are still some large statues, which would look impressive if they weren’t right next to the enormous one. From there we went up a ramp into the Hypostyle Hall, which still has traces of colour in places. Medhat showed us the east wall here, which has a relief depicting a battle – this time not Kadesh, but Ramesses II and his army attacking a Hittite fort at Dapur. The army is shown scaling the walls of the fort with ladders, and you can see the defenders falling off. As well as the large depiction of the Pharaoh in his chariot there are other larger figures (not as big as him tho) who are his sons who led sections of the army – they are labelled with their names. The opposite wall also shows Ramesses II’s sons, in a relief reminiscent of that at Luxor of them all processing. Again they are all labelled, and this time Merenptah (Ramesses II’s eventual successor) has his name in a cartouche – added after his father’s death. I also spent a while looking at the graffiti in this room – there’s quite a variety of it, ranging from roughly scratched names to embellished, dated and carefully carved names. I didn’t spot any ancient Egyptian graffiti in this temple tho.

Next we got taken along by the guardian of the temple to look at a hole where excavations were happening. It just looked like a well shaft, but the rumour was that a mummy and grave goods had been discovered just days before our visit. Later, after we’d come home from Egypt, we read that it was probably (a rediscovery of?) the tomb of the God’s Wife of Amun, Karomama, dating to the 22nd Dynasty. No mummy, but several shabti bearing her name. Still quite exciting to’ve seen, even if we didn’t see anything 🙂

After looking at that we were let loose to explore on our own a bit. There were outbuildings all around the temple which it would’ve been nice to have had a proper look at – they were mudbrick buildings that included storerooms for grain and such, as well as administrative buildings for the temple officials. But the equipment etc for the current exhibition was stored in some of them, so it was off limits to tourists. So we mostly wandered back through the temple taking pictures of it as the sun set – book ending our day rather well, as we’d started with sunrise in Karnak Temple 🙂