At the beginning of April Pierre Tallet talked to the Essex Egyptology Group via Zoom about his team’s work at the harbour of Wadi el Jarf including the papyrus archive that they have found at the site. He talked to us live from Cairo – the team are currently on site at Wadi el Jarf in their 11th season of excavations, but he had returned from Cairo for the day to make sure he had a stable enough internet connection for the talk.

He began by setting the scene – there are three Ancient Egyptian harbours known on the Red Sea coast of Egypt. As well as Wadi el Jarf there is another harbour to the north at Ayn Soukhna (where he has also excavated), and one to the south called Mersa Gawasis which has been known since 1976. These harbours let us know how the Egyptians got to the Sinai and also to the still mysterious land of Punt. Tallet told us that he would only be presenting the site of Wadi el Jarf in this talk.

Sinai is visible from the Wadi el Jarf harbour site, and it’s situated directly opposite a mining site in the Sinai which has evidence of Egyptian use dating back to Prehistoric Egypt. There were regular expeditions to the site from the Old Kingdom onward to mine copper for tools, as well as turquoise. The Wadi el Jarf harbour was occupied in the early part of the 4th Dynasty and most evidence they’ve found dates to the reigns of Sneferu and Khufu. It was abandoned after this, and the harbour that the expeditions used moved to Ayn Soukhna as the earliest evidence at that site dates to after Khufu’s reign.

Tallet told us that the expeditions would’ve left Memphis and travelled by boat down to Meidum on the Nile. From there they would travel by land tracks to Wadi el Jarf through the Wadi Arabah. At Wadi el Jarf the expedition would travel by boat to el Markh – this site was excavated in the 20th Century and dates to the same time frame as Wadi el Jarf. The two harbours operate in tandem with boats shuttling back and forth between them, and they were only occupied and in use where there was an expedition in progress – there were cave systems at the Red Sea coast harbours to store the boats in when they were not in use. Once in Sinai the expedition travels by land to the Wadi Maghara (amongst other sites) where they mine copper and turquoise. There are reliefs at the mining sites from the time of Khufu, which have been known from the 19th Century onward.

The site at Wadi el Jarf was first discovered by John Gardner Wilkinson at the beginning of the 19th Century CE – he found the caves, but thought they were catacombs rather than boat stores. This isn’t surprising as the harbour itself is fairly far from the caves and they are not obviously connected even if you know both parts are there. In the mid-20th Century it was rediscovered by some French pilots – they also didn’t realise it was part of a harbour, but they did find some Old Kingdom pottery and so were able to date it. They wanted to excavate but couldn’t get a commission to do the work (due to the political situation in the 1950s). The current team which Tallet is a leader of began their work 11 years ago after the rediscovery of the French notes and the realisation that this might be an interesting site.

The site is spread over a large area, stretching 15km inland from the harbour to the spring that the Ancient Egyptians probably used. Moving from the coast inland the main areas of the site are: a large artificial harbour, camps and a large building, caves for boat storage (some way from the harbour), a spring which is now inside the St Paul’s Monastery. The spring is the nearest water source, and capable of producing 4m³ of water per day so it must be what they used to keep themselves supplied with water – access to this sort of water source probably helped to determine the site of the harbour.

For the next part of his talk Tallet took us through the main portions of the site in turn (except for the spring). The harbour area was where they started their excavations. It’s the earliest known artificial harbour in the world. It has a large L-shaped jetty which stretches 200m to the east into the sea, and then turns and runs south for another 200m – this protects about 5 hectares of water where boats can safely moor. It’s now normally sufficiently below the water level that you can’t see it standing on the shore, although Tallet said once in 2011 because of particularly low water they were able to see it. But it is visible in aerial and satellite photos. At the bottom of the harbour area there are anchors that were lost by boats using the harbour when it was in use c. 2600 BCE. These are associated with large pottery jars, which were produced locally and probably used to transport water (so used in the boats). Tallet said they have diving specialists working with them to see what can be found in the sea bottom – the plan is that this work will continue next October. They’ve also carefully excavated the part of the jetty that is connected to the land – it was once 10m high and 6m wide, and a lot of it still survives even after four and a half thousand years!

The next area Tallet told us about was the camps, which they are still working on. There are two buildings here, built in dry stones with small internal rooms in rows. There are also a large numbers of anchors in these buildings which look as if they were all left there when the last expedition packed up and went home. His team have weighed all of these anchors and they range from 50kg to more than 300kg – for the whole collection of around a hundred anchors that’s a combined weight of 20 tons! When the anchors were cleaned the remains of the ropes that were used to tie them were found, and also a lot of inscriptions on the anchors (inscriptions were a theme of this talk). These texts date the anchors to the reign of Khufu, and refer to epithets of the king and to the teams who worked at the site. Unfortunately I missed a bit of the talk at this point due to technical difficulties (at my end), but the last thing he talked about in reference to the camps was a document that names the area as Js sḏr which means “the place where one sleeps”. The same document also lists several carpenters’ tools used in the construction of the boats. Tallet thinks that the document is probably about the provision of tools to the workers who put the boats together at the beginning of an expedition, and then dismantled them again for storage after the expedition was finished.

There is a large building situated between the camps and the harbour. It took them 3 years to clear the sand away from the building as it had been pretty well buried. At the time of Khufu this was a large rectangular building measuring about 40m by 60m, subdivided into long thin rooms (each room running the full length of the short dimension of the building). Each of these rooms could shelter 50 men, and it looks a lot like some of the buildings excavated near the pyramids at Giza. Sadly this building had been thoroughly cleared out by its last Ancient Egyptian occupants when they packed up and left, which Tallet said was rather disappointing for them. But underneath this building they have found another level of occupation – and this still had a lot of evidence of its occupation, which was quite exciting! This earlier building dates to the time of Sneferu (the predecessor of Khufu). They have found many ostraca dating to the time of Sneferu with inscriptions. One set are probably ration tokens – each has two sorts of inscription on them, one starts with a circle followed by numbers, the other starts with an eye followed by numbers. At this time an older measure was being replaced by a new standard measure called the heqat, and Tallet thinks the two different sets of inscriptions relate to the two different measurement systems. So as well as being ration request tokens these may also act as conversion notes. As well as these there are also other ostraca that have the names of work teams, or the names of officials with their titles. One of the latter names someone as “the Hunter Tekhy”, and his personal name translates as “the Drunkard”! Another recent find at this part of the site is a shell (from the Nile Valley rather than local) which contains traces of both red and black ink on opposite sides of the shell. Tallet thinks this is probably part of a scribe’s toolkit – his ink well.

Tallet finished his opening survey of the archaeological evidence from the site by telling us about the cave systems. There are two of these, one consists of 19 caves in a curve and the other is nearby in a line on the wall of a small north-south running wadi. There are 31 caves in total, and most of the work they have done so far is on the first system of 19. This is a large number for a single site – for comparison the slightly later site at Ayn Soukhna has only 10 caves. Tallet said that this was the sort of gigantism that is a symptom of the period in general – everything is done on a much larger scale. These caves are not natural, they are long straight galleries cut up to 30m straight back into the rock. Each one was able to be closed with a large plug of limestone, and the team have found the wooden rails which were used to manoeuvre the large blocks into place. The entrances were also hidden from the casual observer. This was all done to protect their possessions – in particular the precious boats – while the site was not in use for expeditions. When they came to excavate them the boats were no longer there – all the reusable parts had been taken away at the end of the last expedition from the harbour. Wood was very precious, and wood suitable for boats like these had to be imported from places like Lebanon. So there were only a few small and broken parts left behind in the caves for Tallet’s team to find.

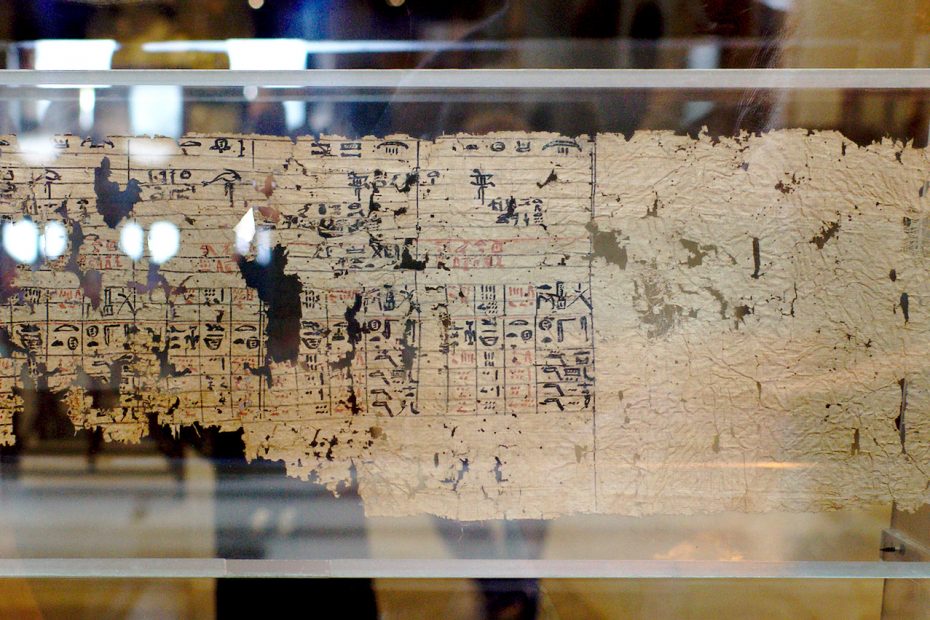

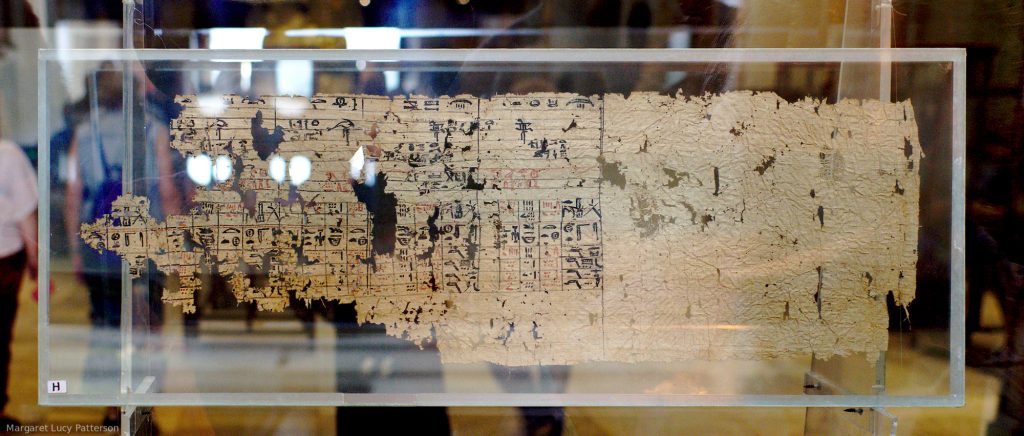

The second half of Tallet’s talk was about the things that were left behind in the caves for them to discover – most importantly a papyrus archive, consisting of thousands of fragments, which was found at the mouth of one of the caves in 2013. The bulk of these pieces of documents have been put in 70 frames of glass to conserve and store them, and they are working on deciphering and piecing together the fragments (which range from small pieces to more substantial sections of papyrus like the one in my photo). They are the records of a single team of workers who went on the expeditions and did other work involved in the building of the pyramid of Khufu. Tallet said they have no idea why these documents were left there at the end of the last expedition from Wadi el Jarf. He returned to this in the questions session afterwards – whilst it’s not clear why the papyri were left behind he does know that they were written up every day (from examining the text, looking at the ink). So this means that it’s not surprising that Merer would have them with him at Wadi el Jarf while he was working there, the mystery is just why they were abandoned. At one point Tallet says he wondered if it was because Khufu died and so the administrative changes with a new reign meant the documents were no longer needed, but evidence discovered in 2017 shows that Khufu reigned for at least one more year after the document date (see below) so that seems implausible.

The documents are mainly administrative documents, dating to the “year after the 13th census of the cattle of Khufu”. This would be year 26 or 27 of his reign (the cattle census was mostly done every 2 years, tho this is not always the case), which is pretty close to the end of Khufu’s reign (but no longer thought to be right at the end). They name the team who they are the records for as “Khufu’s uraeus is its prow”, and this team designation also appears on lots of locally produced storage jars. The team is run by an Inspector called Merer, and the documents also frequently name a scribe called Dedi. There are 6 papyri which cover the whole of a single year’s work done by this team (my photo is not one of these). Each section has the month as the top row of the document, and the documents each cover 2 months of the year. Below the month is a row with all the days of the month in order, and below each day heading is two columns of hieratic text detailing the team’s activities that day. Each week of 10 days (sometimes referred to as a decade, which I find a bit confusing) is separated from the next by a red line.

In the questions Tallet talked a bit more about the implications of these documents on our ideas of the bureaucracy of the Egyptian government of the time. He pointed out that this is a single team of 40 men, who are producing 6 rolls of papyri per year. The pyramid building works had been going on for the whole of Khufu’s reign, and involved many many of these teams. So there was a lot of paperwork involved. It’s almost a bit odd why not much survives – Tallet said he thinks that the Valley Temples for the kings were their administrative and archive offices as well as cult centres. And those temples were always close to the Nile so were places of relatively high humidity. Not good conditions for the survival of papyri.

The best preserved one details two months in which most of the activities of the team were moving fine limestone from Tura to the pyramid of Khufu, which was probably the last stage of building the pyramid. They were doing two or three trips per 10 day week and the papyrus details the journeys they made to do this. First a day or so spent hauling stone to the boats at Tura, then a two day journey with a rest stop overnight (at a named port), after unloading the blocks at the pyramid they remained there overnight before returning to Tura in a single day where they once again hauled blocks for a day or two before heading back to Giza. The return journey to Tura was shorter because the boats were lighter without all the stone! We know they were travelling with the stone to the pyramid of Khufu because it’s named in the text (as Akhet Khufu), and the other sites mentioned (the quarries at Tura, the places they overnight) are also known in the archaeological record.

The next example of the documents that Tallet showed us names “the director of 6, Idjeru” – the title probably refers to a subset of the team, the crew of a small boat which this man Idjeru was in charge of. He’s sent with his men to Heliopolis to pick up rations for the workers – Tallet emphasised how they are not slaves, these are a well looked after workforce who are provided with good food by the state. Idjeru and his team return from Heliopolis with 40 sacks of bread, which would be enough for the whole team for a month – essentially this is the wages of the workers.

Another portion of papyrus mentions Inspector Merer meeting with Ankhhaf, which is a name that we know from sources outside these texts. Ankhhaf was the half-brother of Khufu and had the biggest mastaba tomb in the Western Cemetery at Giza, a famous statue of him is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His titles included “director of all the building projects of the king”, and it’s thought he might be the architect of Khufu’s pyramid.

The examples so far came from reasonably substantial pieces of papyrus, other fragments are much smaller but they can still be pieced together to provide more information. Some talk about work on the arerwt, which translates as “the portal” – Tallet said that he thinks this is possibly Khufu’s Valley Temple which isn’t well excavated as it’s underneath modern Giza. The fragments of the documents do match well with the fragments of the archaeological record, however. One of these very fragmentary documents that he’s pieced together is another of the 2 month log sheets – despite only having 15% of the document they can have a decent go at reconstructing it because of the standardised layout. One thing that shows up in the fragments of this document, is that it indicates the reciprocal nature of the relationship between the king and the workers – the documents has some notations in black ink which talk about what the workers are doing, and then others in red ink which show what they are receiving from the state in return (like clothing or equipment). Again Tallet was keen to emphasise how these documents show that the workforce were not slaves. The document also demonstrates that this is a multi-skilled team – they are not just stone transporters, they are also involved in the cult of the king during his lifetime. Part of this document talks about one section of the team “doing the ritual” when they are spending the day at the arerwt.

To round up the papyrological section of his talk Tallet took us through a few smaller documents. One of these was an account of the food products supplied for the workers – again indicating they weren’t slaves, as they had access to good bread, good beer and foods like fresh figs. Another document was what Tallet called the most ancient ID card in the world. It wasn’t part of the main cache of papyri that was found, and unlike the other documents it wasn’t rolled up but instead was folded. It names a man called Irw-nefer and lists his titles. He was probably there at Wadi el Jarf to get turquoise from Sinai, and Tallet thinks this document was essentially his passport to show the authorities on his route that he was permitted to travel there. The final example was a list of what Tallet thinks may be desert or foreign places, but it’s so fragmentary that he hasn’t yet managed to work out what it is.

As well as these papyri the caves had other inscriptions on them – literally on the walls in some cases, but also control marks on the limestone blocks which were used to seal off the caves when the site was empty. There were also inscriptions on the few objects left in the caves – on the pottery, the copper tools, the bits of boats left behind, even on pieces of textile. Some of these inscriptions were marks that helped to assemble the larger structure that the piece was a component of, and many were the names of teams. These indicate that the various teams were named after their boats (as well as often after the king) – for instance “the followers of ‘Khufu brings its Two Ladies’”, which would’ve probably had two snakes representing the Two Ladies on its prow. Or “the followers of ‘Great is its Lion’”, which would be a boat with lion prows. Merer’s team’s name was also found on the pottery – it was “The uraeus of Khufu is it’s prow”, which again references their boat. There are also some more enigmatic objects with inscriptions on. They have found about 100 cattle horns, which have the names of teams (and sections of teams) written on them. There are also stones called pillow stones (because of their rounded rectangular shape) which also have names of teams written on them. Tallet said that in neither case do they have any idea what these items are for. And as well as all these objects with team names on there are also clay sealings with the names and titles of officials – and many of these also name Sneferu or Khufu, providing yet more evidence of the dating of the site.

In 2017 the team started to excavate the second set of caves, which also have many of these sorts of finds – pieces of pottery, of rope and of wood. There are also pieces of cloth impregnated with bitumen – presumably used to waterproof their boats. They’ve also found the remains of food, which they have been identifying and this archaeological evidence matches well with the papyrus documents and with the foodstuffs found at Giza from the same time period. Tallet said that they’ve also been working on identifying the types of wood that they’ve found – the results include the usual types such as cedar and pine, but they also include ebony which is more unusual. This is not a wood that’s found in Egypt, and it’s only imported from Punt which means that Wadi el Jarf was also the port from which expeditions to Punt left as well as the Sinai.

Tallet concluded his talk by explaining that all the evidence they’ve collected shows that Wadi el Jarf was part of a complex network that existed to bring the resources of the whole of Egypt to contribute to the building of the pyramid. Wadi el Jarf was a link on the chain that brought copper from Sinai to provide tools for the workmen. Other areas of the country provided other resources – food from the Delta (which also went to Wadi el Jarf for teams there as Tallet discussed earlier), granite shipped from Aswan, limestone from Tura and so on. Before the discovery of the papyrus archive the full extent of this network and its complexity were much less well known.

In the questions afterwards Tallet mentioned that he and Mark Lehner are working on a book about the building of Khufu’s pyramid which is to be published this autumn – I found a listing for The Red Sea Scrolls: How Ancient Papyri Reveal the Secrets of the Pyramids on Amazon which I think must be the book he was talking about.

This was a fascinating talk! One of the things that particularly struck me was that while literacy was presumably rare in the 4th Dynasty writing was ubiquitous. Almost every object that Tallet talked about was written on, and presumably even if the team members couldn’t read or write “properly” they would recognise the set of signs that wrote their own team name so they would know which things were theirs. And clearly this was a society with a very very well developed bureaucracy, the points Tallet was making about the quantity of documentation produced by the pyramid building project were also very striking – the Wadi el Jarf papyri were the sort of discovery that changes one’s perception of a whole era of ancient history.

I also have another blog, where I write articles about Egyptological subjects that interest me: Tales from the Two Lands.