Our July 2021 talk at the Essex Egyptology Group was given by Dylan Bickerstaffe – postponed from April 2020 due to the pandemic. This talk complements the “Royal Ladies of the New Kingdom” study day that he presented for us back in April 2019, providing an extra lecture which there wasn’t time to fit in on that day, but also standing alone as its own subject.

Bickerstaffe began by talking a bit about the site of Gurob – this is the type site for harems, the one that Egyptologists use to determine what they think is “usual” for an Ancient Egyptian harem. The name of the harem at Gurob is Per-Khener n Mi-Wer in Ancient Egyptian. Per-Khener is the word that we’re translating as harem, and Mi-Wer is the name of the place. The site is now underneath lots of Egyptian army structures that they use for conducting exercises, but if you look carefully on Google Maps you can still see the outline of the ancient site. Petrie was the first to excavate here, as at many other sites in Egypt, and following him many other people have also worked at the site – including Barry Kemp, Peter Lacovara, Ian Shaw and most recently by an IFAO funded expedition led by Marine Yoyotte.

He next summed up the general modern view of Ancient Egyptian harems with a quote, which I’ll paraphrase: Khener is usually translated “harem” (per means “house”) and seems to refer to both the place and the inhabitants. However it’s confusing because in English it has connotations of the Ottoman Harem which is all about beautiful women attending to the “needs” of the ruler. In contrast to this the Gurob harem (the Egyptological type site) looks from archaeological evidence to have been populated by a large, privileged and self-sufficient arm of the royal palace.

The rest of the talk was Bickerstaffe looking at the evidence for the institution of the harem in Ancient Egypt and seeing how well it fits with this modern view of the institution as being fundamentally different from the Ottoman Harem connotations. He began with some of the evidence that backs up the idea of Gurob as a place associated with the royal palace and a part of the state economy. First he told us about a text from the reign of Seti II in which a senior member of the harem is essentially bragging about the good quality garments that they make for the king – so this backs up the idea of the harem as an industrial complex, particularly involved in the making of fine linen. He also ran through some of the finds from the site that show that it was associated with the royal family from at least the late 18th Dynasty through to at least the 19th Dynasty. These included a head of Queen Tiye (unnamed, but very similar in facial features and style to a securely identified piece), a vase with the names of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun on it, and a papyrus talking about a Hittite wife of Ramesses II.

Before we can think about how the harems of Ancient Egypt compared to or are different from Ottoman Harems it’s important to know what the Ottoman version was actually like, so Bickerstaffe spent a bit of time telling us about that. The women in these harems were all slaves, and there might be around 300 of them. The Sultans had an overall preference for pale-skinned virgins, but also particularly prized Greek, Albanian and Georgian women. Different women had different ranks, and the lowest ranked slept 10 to a room. If a woman had slept with the Sultan she moved up a grade and was given better quality accommodation. A woman who had a son was of the highest rank, and was given a retinue and a suite – these women were given precedence in order of the age of their son. It was a fairly dull life for most of these women, particularly because most of them didn’t even sleep with the Sultan but were just cooped up in this institution for life. Bickerstaffe said the evidence is many of them ended up having lesbian affairs, or affairs with the eunuchs who staffed the harem (there is no evidence of the use of eunuchs in this role in Egypt until after Pharaonic times). The most important woman in the Ottoman Harem was the Queen Mother, whose title was Crown of Veiled Heads – it’s not surprising that she has ultimate precedence: the king only has one mother, but multiple wives. This was similar in Egypt, for the same reasons. When the Sultan died there was a complete change of personnel in the harem – all the old harem slaves were banished to a place called the Palace of Tears, which was essentially a boarding house for ex-courtesans. Occasionally a favourite would be married off to a favoured senior nobleman (in much the same way that European king’s mistresses might be married off in medieval times), but this was very rare. Bickerstaffe also gave us an example of this harem system breaking down – the mother of the first son of Suleiman the Magnificent was actually deposed by his new favourite, who managed to convince the Sultan to promote her own son to heir. This broke the system of precedence and meant that rivalries and factions formed within the harem, with other women trying to promote their own sons rather than just accepting that age of child determined the social order.

The word “harem” derives from an Arabic word, meaning “forbidden” or “inviolate”, thus it’s applied to this group of women who you’re not allowed to visit. In Ancient Egyptian there are a couple of words that are used for what we refer to as harems – ipet and per-khener. Ipet means “private” as well as “harem”, and refers to secluded places. Per-khener also has meanings of “restrain” or “confine”, and generally refers to an institution connected with the royal women. So these do have some similar meanings and connotations to the Arabic “harem” (and the Ottoman Harem). There are also other connected words: khereneru is used to refer to a female troop of musicians or entertainers, and khenywt are women who are singers (or we often translate it as Chantress). Bickerstaffe noted that these words may refer to a respectable occupation, but may also be a euphemism for a less respectable woman. This is similar to the way the word “actress” used to be used in English (during the 17th Century CE, for instance) – some women called actresses were respected actors who happened to be female, and sometimes actress was a euphemism for prostitute.

Bickerstaffe now moved on to talk about the Tale of Sinuhe, which is an Egyptian story set in the Middle Kingdom at the transition from the reign of Amenemhat I to Senwosret I. This has quite a lot of passing mentions of the institution of the harem, so it gives us a good flavour of how the Egyptians themselves talked about it. Sinuhe’s title at the beginning of the story is bꝫk n ipꝫt nsw, which means “Servant of the Royal Harem”. His titles also refer to him being the Servant of the Hereditary Princess, the Greatly Praised Royal Wife of Senwosret I, Royal Daughter of Amenemhat I, Neferu. Whilst it’s not made clear if this is one job or two separate roles it seems most plausible that it was a singular position and that Neferu was the woman in charge of the Royal Harem. It’s clear from other parts of the story that he’s closely associated with the Queen, and it’s also clear that he’s involved with the Royal Children. Whilst he’s on campaign with Senwosret I (during the early part of the story) so are some of the Royal Children, and he receives messages from others. In the later part of the story when he is being encouraged to come home the messages he receives are again from the Royal Children. Possibly he’s even a blood relative of theirs. At the end of the story when he does return it is the Royal Children who welcome him back, by shaking their sistra and dancing. From this story Bickerstaffe said we can glean some information about these Royal Children – sometimes it is clearly referring to boys (as when on campaign) but other times girls (when they dance with their sistra). But it’s ambiguous as to whether they are actually all children of the king, or whether this is a title/role.

Royal Nurses are also a key part of this institution. The harem is an enclosed or exclusive place, and the Royal Children seem to be brought up there, or at least associated with it. These children probably saw their nurses rather more than their parents, so these nurses were very important and very influential on the elite of Egypt. Bickerstaffe gave us a few examples of these important women. One is the wet nurse of Ahmose-Nefertari (first queen of the 18th Dynasty) who is buried with all honours, and even ends up in the royal mummy cache (so even the later Egyptians regarded her as significant enough to preserve). Another mark of favour was given to the wet nurse of Hatshepsut – there is a surviving high quality statue of her. There is also a body, found in KV60, of a woman with the same name and the title of Wet Nurse – she is sometimes assumed to be the same person, and thus used to argue that the other female body in that tomb is Hatshepsut, however Bickerstaffe is very dubious about the plausibility of this. He thinks it’s much more likely that this is a different woman. Another favoured wet nurse is Maya, who has a very fine tomb at Saqqara and in this tomb there is an image of her with Tutankhamun sitting on her knee, which displays her closeness to the king.

Thus far most of Bickerstaffe’s evidence fits the idea of the Egyptian harem as an arm of the Royal Palace, but now he moved on to other evidence that suggests a more Ottoman Harem interpretation. He began this with what he referred to as the story of Sneferu’s boating beauties. In the story Sneferu is feeling glum, so his lector priest suggests that Sneferu should fill a boat up with his beautiful ladies and watch them row up and down because the sight will cheer him up. So Sneferu orders this to be done, and the boat is filled up with nubile young women. The way these women are described they are very clearly not the weavers of fine linen, but instead are the king’s sexual partners. The story continues to tell of one of these girls losing a pendant in the water and stopping her rowing, and so the king offers to gift her a new one. But she is insistent that only the one she has lost will do, and so the lector priest magically removes half the water in the lake so that the pendant can be retrieved (before putting the water back in so the rowing can recommence). So this story implies that the kings of Egypt had harems in the Ottoman sense!

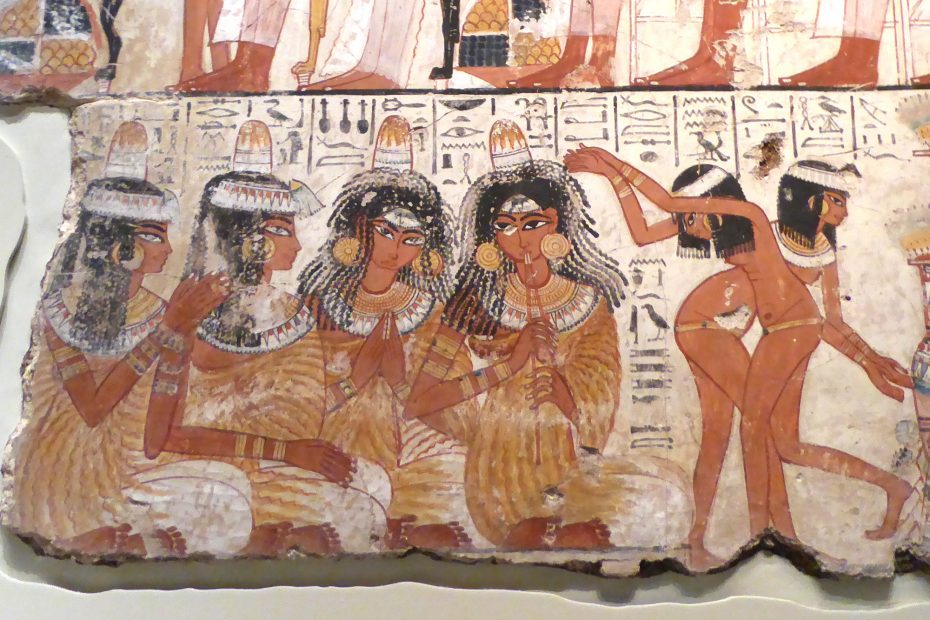

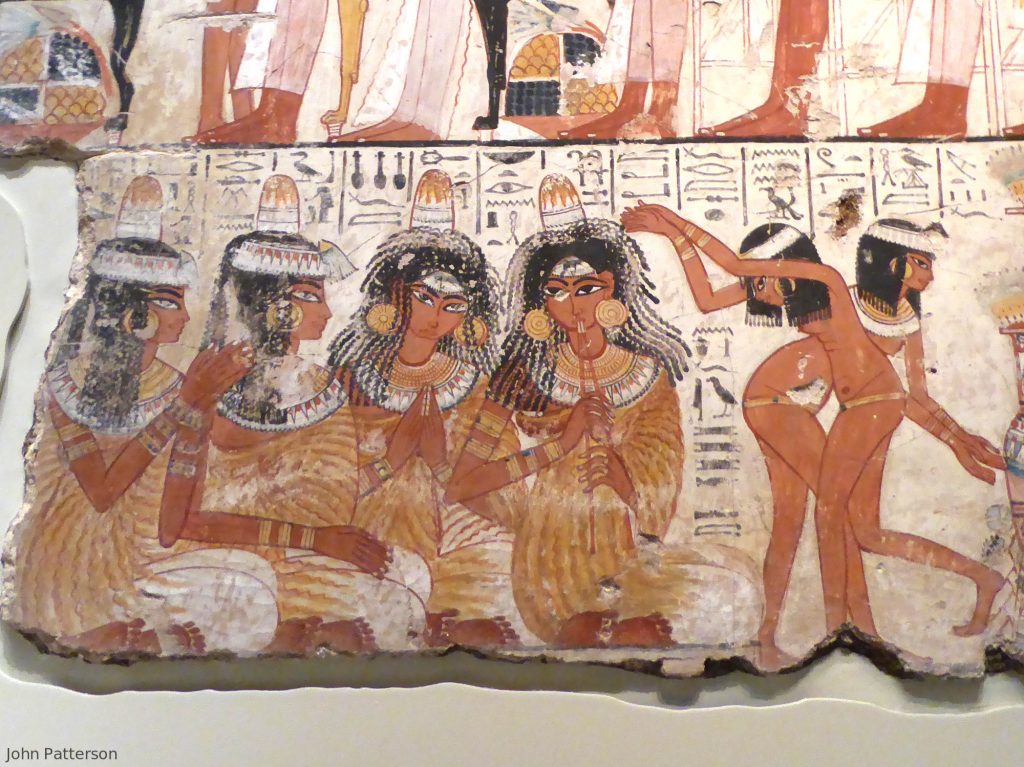

There is also archaeological evidence for the existence of women who were the king’s concubines rather than part of the linen manufacturing business. The first example Bickerstaffe gave us was of the three princesses or wives of Thutmose III, whose tomb was found in 1916 by locals after it had been exposed by a storm. The Metropolitan Museum of New York bought up the stuff that the locals were selling, and persuaded them to tell the Museum where it had been found. The tombs were subsequently excavated by the Museum and the burial goods are now on display there. Bickerstaffe said that these women were clearly women of the harem, and they had been given very nice burials. Each of the women was buried inside 3 nested coffins, which were placed side by side in the same tomb chamber. The wooden items of the burial goods had perished due to flood damage over the millennia but there was a lot of gold left – the locals were said to have been particularly impressed by the golden sandals. And the women were also buried with golden toe and fingers stalls, as well as a lot of jewellery, fine alabaster and other stone vessels. Howard Carter described the women as “the harem women of Thutmose III”, and Gardiner confirmed that these three were otherwise unknown from textual sources. They had names that suggest a Syrian or Levantine origin – Menhet, Menwi and Merti (the last of which we would render “Martha” today).

These women were quite possibly an example of what Bickerstaffe referred to as “brides by post”. There is a lot of evidence for such women in the Amarna letters. Bickerstaffe said you could summarise a lot of the correspondence as the Egyptian kings asking their correspondents to “send me women” (often specifically asking for daughters or sisters), and the foreign kings asking for gold and complaining about the quality of the golden objects they received! Minor kings and other lesser correspondents of the Egyptians just sent their daughters, but the more major kings expected a quid pro quo in the form of significant quantities of gold.

Other evidence comes from jewellery associated with the Amarna royal family. There’s a collection referred to as the “royal jewels of Amarna”, which are thought to’ve been found at Amarna (but the circumstances are somewhat confused). These included some rings that were once thought to’ve been much more recent, perhaps dating to the Coptic Period, but are now thought to be foreign – so evidence of women at the royal court from foreign places (perhaps Cyprus). Some rings had the name of Nefertiti on them – Bickerstaffe said that this isn’t an indication that they belonged to her, instead it was the sort of thing that she would give out as a mark of favour to a servant or client (this is like the Gold of Honour that the king would give to favoured courtiers – it always had the king’s name on it). Other Amarna jewellery includes four necklaces which are now at the Egypt Centre, Swansea – these are said to have come from the burials of four Amarna princesses (although the actual provenance is unknown, this is what the first buyer was told). It’s not clear if these were daughters or harem women, nor is it clear where their tomb might be – perhaps further into the wadis where the Royal Tomb is.

There are palaces at Amarna that are linked with the harem as an institution, as well. The Northern Palace is often thought to be the palace of Nefertiti, and is sometimes also called a harem palace. It seems to’ve been under the control of the queen – this is very like the Royal Children in the story of Sinuhe (who are, for instance, called in by the Queen to welcome Sinuhe home as well as his title referencing the Queen as well as the Harem). There is also another harem palace, in the centre of the city there’s a building called the Northern Harem Palace. Its floor plan includes a court with little rooms round the edge – this is sometimes interpreted as being for the king’s women, but Bickerstaffe pointed out that it might as easily be a whole set of storerooms round the open court. Other evidence from Amarna includes a representation in the tomb of Ay of a palace harem scene, which has a bed prominently in the scene. So there does seem to be some sort of a harem of women available to Akhenaten, and it’s quite clear that he’s not faithful to Nefertiti! As well as the harem under the control of Nefertiti the titles of an official indicate there also appears to have been some sort of harem under the control of Tiye – even once she’s the Queen’s Mother rather than the Queen. And as well as these institutions in Amarna there were almost certainly other harems at other royal palaces around Egypt – even Akhenaten didn’t remain in one city all the time.

The tomb of KV40 in the Valley of the Kings gives us some idea of the sort of people associated with the harems of the 18th Dynasty. This tomb (and KV64 next to it) has recently been excavated by Susanne Bickel (which she spoke to us about in April 2018). There are a mixture of sorts of people buried in the tombs – weavers, queens, royal children, and bed partners – with one senior woman buried in KV64 and many other individuals in KV40. The burial goods from KV40 had names and titles of these individuals, and the titles and dating suggest that this was the harem of Amenhotep III. There are at least 30 individuals in the tomb, with several princesses and princes whose titles indicate their affiliation to the “household of the Royal Children”. There were also several foreign names, corroborating the evidence from the Amarna letters of the Egyptian king requesting women to be sent.

There are more burials near where the three minor wives of Thutmose III were found – Bickerstaffe showed us photos of the wadi taken while he was walking on the paths up on the mountains. There are pieces of canopic jars from these tombs with names and titles on, which had been dug up by locals and sold. As with the goods from KV40 these include princesses & princes, and also queens – such as Queen Henttawy or Prince Menkheperre. There are also women whose title is “Royal Ornament” such as “Royal Ornament Sitti of the Queen’s House”. This is one of those titles where it is sometimes respectable and sometimes rather less so – and the nicknames recorded on the grave goods can help us see which implication is intended. For instance Sitti is called the “frenzied thrasher in the city of the dazzling Aten”, and Bickerstaffe gave us a couple more examples that I didn’t note down. It’s hard to escape the idea that these suggestively named women were the bed partners of the king.

Bickerstaffe wrapped up this section of the talk with a few more examples from the Amarna letters – for instance a request that a foreign ruler should “send extremely beautiful female cupbearers in whom there is no defect” as a quid pro quo for some goods (valued at 160 deben). And these are requests that we know are answered – there are letters that explicitly say that they are “sending on 10 women”, for instance. Taken altogether the evidence Bickerstaffe presented builds up a picture of a household of attractive women who were there explicitly for the king’s pleasure, not just to make him fine linen.

The next section of the talk moved on to another aspect of similarity that Bickerstaffe sees between the Ottoman Harem and the Egyptian harems – harem conspiracies. The earliest one we know about is during the reign of Pepi II in the 6th Dynasty (c. 2200 BCE). The autobiographical text in the tomb of a Senior Warden of Nekhen called Weni mentions it. As is the norm in autobiographical texts from these period Weni spends some time bragging about how great the king thought he was, and part of this contains interesting information about the harem of Pepi II. Weni talks about being trusted to judge a “secret” of the king’s harem, and it’s thought that this was a conspiracy by one of the women who was a part of the harem.

Another famous harem conspiracy is the one that results in the death of Amenemhat I. This is an important part of the setting of the Tale of Sinuhe which Bickerstaffe had told us earlier in the talk – the news that comes to Senwosret I (and thus Sinuhe) while on campaign is that Amenemhat I has been assassinated, and this is why Sinuhe flees to foreign lands. It’s also mentioned in another text – this one purporting to be the instructions of Amenemhat I to his son Senwosret I, telling him how to be a good king. As with the autobiography of Weni this is a standard text form of wisdom being passed on from father to son, but again as with Weni’s autobiography the details tell us more about the historical setting for text. In this case the instructions talk about Amenemhat I having been killed in his bed by a conspiracy of women while the heir (Senwosret I) was away on campaign, but the conspiracy was ultimately unsuccessful because Senwosret I came back from campaign and reclaimed his throne from the usurper.

The most famous harem conspiracy is, of course, the one that was launched against Ramesses III and Bickerstaffe spent a while talking about the details of this. The conspiracy is thought to’ve taken place at Medinet Habu, and there are two areas of this temple complex that appear to’ve housed the institution of the harem. One of these is in the gatehouse of the complex – on the outside there are war scenes showing the king’s power in battle. But inside the rooms the decoration shows the king seated with girls bringing him drinks, food etc – and some of these women are dressed as if they were foreign princesses. The other place is in a destroyed part of the complex, but a team from the University of Chicago (based in Egypt at Chicago House in Luxor) have been putting what remains of the scenes back together. The texts sometimes refer to the women as the Royal Children, so this is still the title associated with these institutions in the late New Kingdom.

Bickerstaffe explained that Ramesses III had made his own life difficult, and set up the conditions that bred the harem conspiracy. Unlike the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman that he talked about earlier in the talk Ramesses III’s problem was his refusal to name an heir or given any particular woman prominence. There are reliefs in the temple where a queen is represented and labelled with the title “Great Royal Wife” but the cartouche that follows is blank – what is represented is the office of queen, but no individual is named as filling it. He did the same with his sons – following Ramesses II’s example there are reliefs in the temple showing processions of sons, but unlike in the earlier examples the young men aren’t named. If you visit now you will see names, but this is because after Ramesses III died the sons who took the throne in succession added their names to the reliefs. So Ramesses III was trying to avoid naming an heir, in order to keep power firmly in his own grasp. But this backfired and lead to a group of people, including one of his queens and her son, plotting to kill him and seize power.

We know the names of two of Ramesses III’s queens – one is a woman buried in tomb QV51. This tomb is very damaged but still has the smashed up sarcophagus of the queen and we know that she was called Isis. Another wife, who is also buried in the Valley of the Queens, was called Tyti. Isis was probably the senior queen, even if she was never officially given that status. Bickerstaffe said that because it is likely that Tyti was the woman who is named in the documentation we have for the harem conspiracy – although the name given for the queen is Tiy this is likely to be a pseudonym.

We actually know quite a lot about who was involved in this conspiracy because the records of the trials of the conspirators have been found. One section of these records lists all the condemned, with their names, occupations, crime and punishment. The names given are mostly pseudonyms – recording and speaking the name of a deceased person helps keep them alive in the afterlife, so it is something to be avoided when said person has committed a crime. The Egyptians didn’t want their records of crimes to be helping the criminals in the afterlife! So one man is called “Paibakkamen”, which literally means “The Blind Servant of Amen” and is probably pseudonym for Pabakamen (which means “The Servant of Amen”). Most of them are these sorts of insults based on the real name of the person in question. Another example is a man whose name is recorded as “Mesedsure” (meaning “Re Hates Him”), who was probably called “Meryre” (= “Beloved of Re”) in reality.

The first list of names are the people who were executed for their involvement. The crimes these people are convicted of cover quite a range. One man is the captain of archers in Nubia, and he is accused of planning to bring his troops to fight alongside the conspirators. There are also several Inspectors of the Royal Harem, whose crime is non-disclosure. And also wives of the “men of the gate of the Harem” who are also executed for their collusion. The next list has the names of those who were condemned to commit suicide in public – this included an army commander, and some sort of magical priest. The latter was involved in performing magic to affect the outcome of the conspiracy. The third list were also condemned to commit suicide, these individuals could not only choose the manner of their death but were also permitted to do so in the privacy of their cells rather than in public. This list included Pentawere, the prince who was involved in the conspiracy and this is where the queen who was involved was named as Tiy. The people on the last two lists did not die – the fourth list named several of the judges of some of the earlier courts in the process who were thought to’ve been corrupted by associating with the accused. They had their noses and ears cut off. And lastly was one lucky man who was accused of having been “associated with the above” and he got away with being “told off with bad words”!

As well as the lists of the condemned several of the individual indictments also survive and Bickerstaffe talked us through a few interesting examples. They follow a fairly standard formula – the “great criminal” whomever is accused of a specific crime, and then it says this person was tried, found guilty and that his “punishment came upon him”. Paibakkamen, for instance, was accused of collaborating in the conspiracy. Another man was accused of making some magic writing, and making some wax gods and potions for the disabling of the limbs of people – basically providing magical assistance to the conspirators.

Another is said to have “caused a going forth against the Royal Bark and it was overturned”. This might be intended literally – the Royal Bark would’ve been carried in procession during festivals, and the conspiracy is said to’ve coincided with a festival. Bickerstaffe showed us a descendent of the sort of festival held in Egypt – in modern Luxor model boats are still carried in procession during religious festivals. They are right in the middle of a crowded gathering so it would be easy for someone or several someones to get close and knock the boat off the shoulders of those carrying it – creating a disturbance that would call troops away from their posts. But it might also be a euphemism – if writing causes things to live forever (as the Egyptians believed) then writing down the killing of a king would be avoided as it would make it permanent. So saying that someone “overturned the Royal Bark” could be a circumspect way to refer to it.

Yet another person is accused of having given the conspirators magical assistance and also of having given them papers to let them access the harem – essentially headed notepaper that they could write their own passes on. Bickerstaffe gave us another modern parallel here, from the UK this time. In 2004 some hunt saboteurs stormed into the House of Commons while it was in session in order to stage a protest (and get themselves and their message in the media). They had got entry to the building using both the ruses that the harem conspirators are accused of using – there was a large and noisy disturbance outside the building caused by other protesters which kept the police occupied. They also had used some House of Commons headed notepaper and forged an invitation from two (genuine) MPs to a meeting inside the building – once inside they were able to get someone to let them into the debating chamber, and then staged their protest.

The harem conspiracy against Ramesses III appears to’ve been successful. The mummy of the king has been scanned and shows a large and deep wound across his neck, and Bickerstaffe says that he is reliably informed that it must’ve happened while the king was alive because of how the tissues have pulled apart. There’s also an amulet that was inserted during the mummification process in order to “heal” him in the afterlife. The identity of his son Pentawere is a matter of some debate – one possibility often put forward is a mummy referred to as Unknown Man E. This mummy is contorted, so is sometimes called the “Screaming Mummy”, and was found wrapped in a sheepskin (which is very unusual and may’ve been considered unclean). Those two facts are cited as reasons this was the mummy of someone who was being “punished” in the afterlife, but Bickerstaffe thinks that they aren’t really evidence. The posture is a natural consequence of desiccation without proper mummification procedures not a sign of a terrible death. And the mummy was found in a good quality coffin in the cache of royal mummies that was found at Deir el Bahri – which would be an odd mark of respect if the priests doing the reburial thought this was a father-killing prince (and it would be reasonably recent history for them). Sheepskins are also used in burials of some other cultures that the Egyptians had contact with – like people in the Aegean and the Levant. So Bickerstaffe suggested that maybe this man was a foreign prince, or the son of a foreign princess, or even someone who died abroad and was treated with that culture’s version of respect before being sent to be buried in Egypt.

There might once have been evidence from the place he was buried – the body of Pentawere was supposed to’ve been buried next to Ramesses III. But that information is now lost. Both Ramesses III and Unknown Man E found in the royal cache at Deir el Bahri rather than their original burial sites. And even if those moving the bodies had taken care to keep groups together the “excavation” of the royal cache was not as well documented as a modern excavation would’ve been so we don’t know which mummy was found where. For instance Bickerstaffe says he thinks the fact that the body of Ramesses III was found in the coffin of Ahmose-Nefertari is an artifact of the removal from the cache – that the excavators tucked him into the large mostly empty coffin alongside the queen because it would be easier to carry out!

Bickerstaffe also briefly discussed the DNA evidence for a relationship between the two mummies – a study was done that looked at their Y chromosomes (amongst other things), The published results show that the two have the same paternal lineage (so could be father and son) but Bickerstaffe said that there are many doubts about how the study was carried out (in particular that they went looking for a relationship rather than getting the data first then analysing it). Also the haplogroup that was attested is one found mostly in west and south Africa, rather than the east of the continent – which does seem a trifle implausible and perhaps suggestive of contamination.

To wrap up the section on harem conspiracies Bickerstaffe turned to a story in a text called the Instructions of Ankhsheshonq. These instructions are said to be written by a man named Anksheshonq who got into some sort of trouble that meant he had to flee from Heliopolis to stay with a man called Hariese. But it turned out that Hariese was involved in a conspiracy to kill the king! Ankhsheshonq admonishes him and tells him to stop being involved, but Hariese says that everyone’s in on it. Unfortunately their conversation was overheard by a man called Wahibre-makhy the son of Ptahhertais, who disclosed it to the king. Hariese is arrested and confesses, and then he and his fellow conspirators are burnt at the stake – this is probably the punishment that the conspirators against Ramesses III suffered if they were executed. It’s a particularly cruel punishment for an Egyptian, as it also removes your chance of a successful afterlife because you no longer have a body for your ba and ka to reunite with. Ankhshehonq is not executed but he’s taken to the houses of detention in Daphnae – basically sent to the back of beyond for the crime of not disclosing his knowledge of a conspiracy. The text even explicitly says that he is not released on the anniversary of the Pharaoh’s accession which indicates he’s still in serious trouble. It’s whilst in detention that he writes down this text of Instructions.

Having shown us how many parallels there actually are between the Egyptian harem and the idea of the Ottoman Harem Bickerstaffe concluded his talk by showing us a map with all the known Egyptian harems and known locations of harem conspiracies marked on it. He pointed out that the vast majority of them are associated with royal centres, places where the king spent significant amounts of time. The only exception to this is Gurob. So Bickerstaffe’s conclusion is that we are blinding ourselves to the reality of the Egyptian harem by our choice of type site. He believes Gurob more closely matches the Ottoman Palace of Tears – the retirement home for the concubines of the previous king – rather than a normal harem. So it is not a good type site for how the normal harems operated – they would be full of nubile young women who were there for the pleasure of the king and only once they were surplus to requirements would they move to Gurob and become weavers of fine linen garments for the king.

This was a really interesting look at this aspect of Ancient Egypt, pulling together several strands of evidence to suggest that maybe the early Egyptologists weren’t just being prurient Orientalists in their portrayal of the Egyptian harem! As well as sounding a cautionary note about extrapolating too far from a single site before you’re entirely sure if it’s the exception or the rule.