At the beginning of December Dr Daniel Soliman spoke to the Essex Egyptology Group via Zoom about his work on literacy at Deir el-Medina, a topic which he told us was very dear to him. He has mostly been using ostraca to investigate the topic – there are many that are marked with signs and tally marks rather than the hieroglyphs and other scripts that we are more familiar with.

Soliman began by giving us a brief introduction to the site of Deir el-Medina, which is situated in the western Theban mountains (and he had a lovely photo of the village from an angle I’ve not seen much, clearly showing it nestled in the hills). The name, Deir el-Medina, is a modern name but the village is ancient. It was an extraordinary settlement which was founded by the state to house the workmen who worked on the royal tombs for the New Kingdom kings & queens – and their families. It existed for several generations, covering 4 centuries, and archaeologists have found a lot of information about this people and the details of their lives. This gives it a special place in Egyptology.

It is assumed it was founded during the reign of Thutmose I (who was the 3rd king of the 18th Dynasty, ruling c. 1500 BCE). The primary evidence for this is that there are mudbricks in the walls of the houses stamped with his name so those walls were built in his reign. Soliman said he wasn’t going to talk too much about the 18th Dynasty today, because even though it’s interesting it’s its own story, instead he focused on the Ramesside Period.

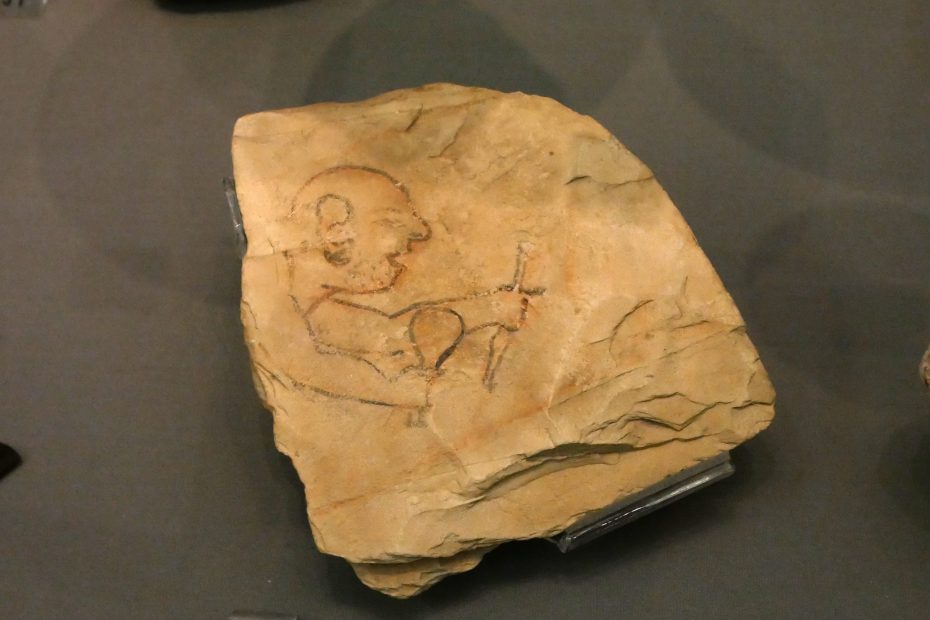

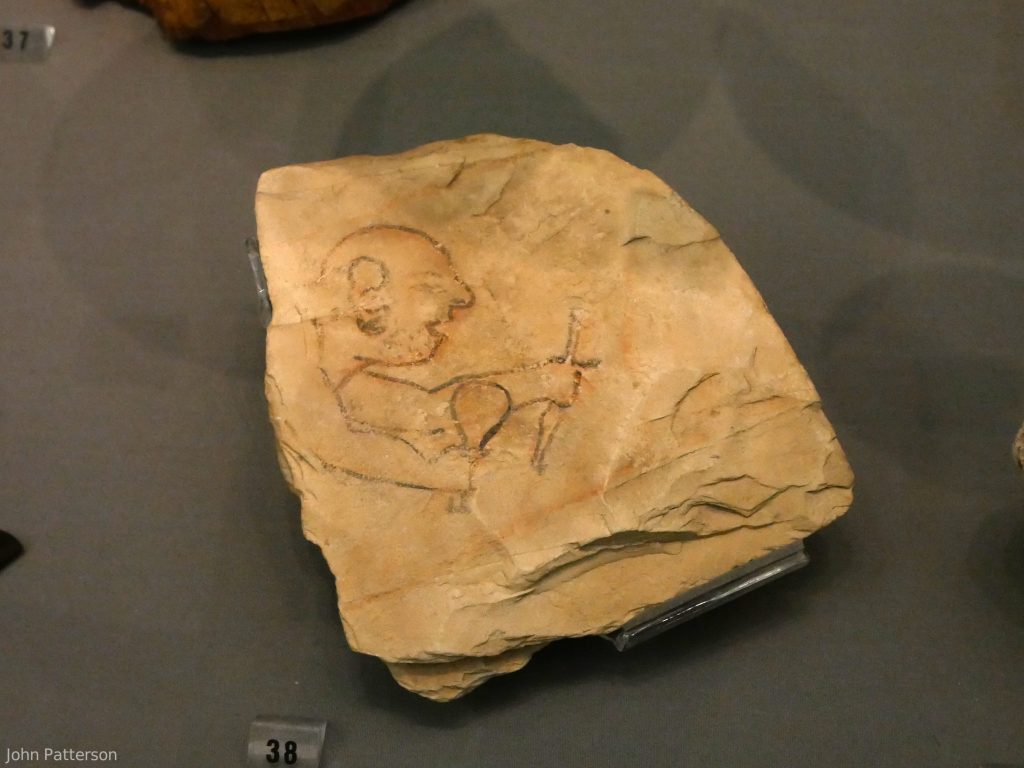

The village is situated where it is, because of the proximity to the two Theban valleys where the royal tombs were situated. It’s also set apart from other communities and guarded, so it is a secluded place where only a particular set of people had access. The people who lived there were, as he had said earlier, the workers employed by the state to build and decorate the royal tombs. These are very ambitious rock cut tombs with multiple galleries and chambers, and a lot of the workers were employed to cut these spaces into the hillside. Soliman showed us a photo of an ostracon from Deir el-Medina (now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, see John Patterson’s photo above) which depicts a caricature of a labourer of this time. He’s holding his hammer and chisel, and is a bit stubbly with his mouth open and with muscular arms. As well as the many manual labourers there were also highly educated and specialised workers – these people had access to a lot of written material: to the funerary texts and other knowledge that they used to decorate the tombs. So this is a varied bunch – mostly manual labourers, some artists and some administrators – and in this specialised community all of them came into contact with written material on a daily basis (unlike in a more typical farming community).

In this small village community there are not just these workers, there are also their wives and their children. However Soliman said he was going to mostly talk about the workmen themselves. Even though there’s a a lot of data about the lives of the women in the community (especially as compared to other sites) the men are nonetheless better documented. And particularly relevant to this study, where he’s considering their relationship to written material, is the fact that the documents are primarily written by the men.

Soliman told us that we know quite a bit about the structure of the village that these people lived in. The buildings survive to quite an extent, and so do the rubbish dumps – these give us a lot of interesting material from rubbish through to a lot of the written material. Their tombs, chapels and religious structures also survive, as do stelae etc from such places. Amongst other things that gives Egyptologists a lot of names and relationships to work with, and so it’s possible to construct family trees over many generations.

As he said, he was concentrating on the Ramesside Period, which we know more about than the 18th Dynasty. It seems like literacy in the 18th Dynasty was much lower – possible the workers themselves weren’t doing any of the writing in this earlier period but instead the administration etc was done by outside officials who visited to make reports. But in the Ramesside Period the administration was done by local scribes & officials.

Soliman next told us what we know about how work and life at Deir el-Medina was organised. The crew of workers was divided into two “sides”, the right side and the left side. Each of those had a foreman and a deputy. There was also a chief scribe and his apprentice (and later in the 20th Dynasty there were two chief scribes). These half a dozen men were the management team. There were also other people who called themselves scribes, and who produced hieratic documents. For instance deliveries to the site were recorded by a scribe (foodstuffs like bread, vegetables, fruit, water, and maybe meat & wine were transported form the temples in the vicinity), there were also draughtsmen who worked on the decoration of the tomb (which would include a significant amount of text), as well as other scribes and low ranking functionaries. So there are a significant number of people involved in the formal administration of Ramesside Period Deir el-Medina, who produced hieratic documents on papyrus and ostraca.

After these preliminary remarks Soliman moved on to the meat of his talk. He was looking at the question of literacy, and to some extent using Deir el-Medina as a case study for the rest of Egypt (although this is difficult due to the differences in their situation). The key study in this field is by John Baines and Christopher Eyre: “Four Notes on Literacy” (which is available in “Visual and Written Culture”, a collection of articles & essays by John Baines), and much of the rest of Soliman’s talk was in dialog with this study. In their analysis of literacy at Deir el-Medina as part of this article they discuss two groups – those that are “fully literate” and those that are “literate to some extent”. They estimate that there were 18 to 20 individuals who were fully literate – these include the half a dozen man management team that Soliman had described above plus at least one draughtsman, as well as 12 men who were the sons and apprentices of these men. These individuals had formal training, and were able to produce properly written and formatted documents in hieratic. The total number of men who were full members of the crew was on average 45 – Soliman made a point of stressing that this is an average, it varied over time. There were also on average 25 service staff members, who probably didn’t live at Deir el-Medina but were involved in delivering commodities to the village. So that suggests a literacy level of 25-30%, which is incredibly high for an ancient society (we think!).

Baines and Eyre also suggest that the kinsmen of these fully literate members of the crew were also literate to some extent. So Soliman said that the first question to think about is what do we mean by “literate to some extent”? And he was going to begin to think about this by looking at what we actually mean by “fully literate” in the context of Deir el-Medina. A modern collection of papyri called Chester Beatty papyri include a set of papyri that were once a private library assembled by a scribal family living in Deir el-Medina over several generations. This includes many different types of document – private letters, administrative documents, school and other instruction texts, literary stories, hymns & rituals, and magical & medical texts. So this is what “fully literate” looks like at Deir el-Medina – this is the sort of thing that fully literate person owns, can create and can read. However Soliman pointed out that it’s not just the fully literate that had access to all these texts. This library had been owned by a family over generations, and we know that not every generation included scribes – sometimes they were workers or draughtsmen. So even some people who weren’t in the “fully literate” category had access to a full range of literary texts (and regarded them as important to preserve for future generations).

Soliman next moved on to consider the difficult to grasp concept of “literate to some extent” directly. This is not a single state – it’s a spectrum, and a very broad one. Baines & Eyre suggest that some workmen could write their own names, and that was it – and there are lots of graffiti of workmen’s names found at and around Deir el-Medina. The are written in a fairly informal and disorganised fashion, not in the same way that a trained scribe would write the names. There are also, in this graffiti corpus, identity marks – these are signs which aren’t words or names, but were used by individuals to identify themselves. It is these identity marks which Soliman is focusing on, and the rest of his talk was to look at how these were used over the Ramesside Period (covering them not as a chronological sweep but thematically). He recommended a book on the subject “From Single Sign to Pseudo-Script: An Ancient Egyptian System of Workmen’s Identity Marks” by Ben Haring, which he said is both comprehensible and thorough (and sadly also eye-wateringly expensive as academic texts often are).

Baines & Eyre don’t discuss identity marks in detail – they mention them briefly, saying that most workmen weren’t literate to any significant degree and used marks to label personal property in the domestic context. They also suggest the use of these marks might relate to the non-literacy of women. However Soliman disagrees with this assessment, as his work shows that fully literate workmen also seem to use identity marks particularly when recording things together with people who were not fully literate.

Soliman now showed us some examples of items with these identity marks on them. He began with a folded piece of linen with a mark on it – this is an example of using a mark to indicate ownership of property (and this particularly item came from an 18th Dynasty tomb). The mark is a geometric mark, it doesn’t look like the man’s name or any other sign in any Egyptian script, but instead is abstract. This isn’t the case for all marks – some do look like hieroglyphs or groups of hieroglyphs which are related to the name of the workman (or his nickname, or his job). So there’s a spectrum of marks – some relate to the person and are almost readable as text, some don’t. There’s an added wrinkle in that the marks can be inherited by a man’s son (or sometimes other workers), and so a mark which was once connected to a specific individual no longer is. The linkage might be restored in the future, however, as names are often inherited – a man named after his grandfather might eventually inherit his grandfather’s mark.

Other examples of identity marks used to indicate ownership that Soliman showed us included a ring stand for an amphora, and he noted that marks are incised in all sorts of pottery objects. There are also tools with them on, as well as other things in domestic contexts. There is also an example of an ancestor bust which has an identity mark on its underside.

There are also a lot of ostraca that include identity marks. Some of these just a single mark on the ostraca, and it is not clear what these are for – perhaps they are tokens, used for receipt of things like copper chisels in order to record who got which valuable item? And this brings us back to the administrative context and out of the domestic one. Soliman said there are around 500 ostraca with identity marks on, and most of these are clearly administrative in nature. He showed us one example from the 18th Dynasty which seems clearly written by someone who isn’t fully literate – the marks are along the broken edges of the piece, not something you’d do if you were accustomed to writing formal documents. Another example has very large signs, so Soliman suggested it possibly wasn’t administrative but was instead intended as a monumental piece – again it has a very disorganised arrangement of signs unlike what a trained scribe would do.

Taking these ostraca as a whole there are some commonalities – pieces from the 18th Dynasty mostly record deliveries of food and other commodities. In the 19th Dynasty they are often lists of workmen. The names/identity marks are not listed in a fixed order, but you do see the same ones on different ostraca – he showed us a couple of examples where some of the names are the same between the two pieces but were very clearly written by a different hand. Some of the signs are obviously not hieratic signs or hieroglyphs, but some of them are and the names are readable (although not always attached to a man with that name, as Soliman had discussed earlier they were often inherited). One interesting identity mark is a sign in the shape of a scorpion. This refers to a particular role in the crew – the man with this mark was the “scorpion controller”, he had the additional duty of catching snakes & scorpions and of handing out remedies to those who were bitten. Soliman also drew our attention to the handwriting on these two ostraca. One of the writers clearly has an eye for detail but his lines are unsteady and scribbly – he’s not used to doing this. But the text on the other ostracon is written by someone with a good hand, that looks practised and even includes features like hieratic ligatures (where two signs next to each other have a joined-up form). So the writer here was probably formally trained and fully literate despite writing this document with identity marks.

Baines & Eyres also discuss other sorts of workers at the village such as the guards (or guardians or gatekeepers) who control access to the village, and they suggest that literacy is irrelevant for that job. So perhaps these men could at best read but not write more than a very small amount. Soliman said that there isn’t any data for this group of village workers, so sadly we can’t do more than speculate.

There is however data for the people who recorded the arrival of commodities into the village. As Soliman had said earlier the village was supplied with food and other necessities (and luxuries) from the mortuary temples on the West Bank of Thebes. These commodities were recorded on arrival and we have many hieratic documents from the 20th Dynasty detailing the deliveries. But these documents are not the original records of the deliveries, they are the good copies made out to be neat and tidy and properly formatted. The originals were written by men who were not fully literate – during the Ramesside Period there was a rota system which each day one of the 19 members of the right side of the crew would stay at the village to receive the incoming commodities. They’d make notes as best they could, then the neat copy would be made.

Soliman gave us a particular example where we even know the names of two of the men involved! During the period from Year 20 of Ramesses III through to Year 1 of Ramesses V several hieratic records of commodities survive which were written by a man called Hori, the name of the man who wrote the original records is probably Pentaweret (I think I got that down right). These originals are in a psuedo-script consisting of some hieratic signs, some ID marks and some self-made signs. There are several interesting quirks to the texts which tell us the writer hadn’t had formal training – for instance the dates. He knows how to write a regnal year, and sometimes he indicates the month or the festival at the start of the month using an abbreviation of the name in hieratic signs. But the abbreviations he uses aren’t the standard ones that scribes get taught to use, instead he’s invented his own. Similarly for the day he writes a non-standard abbreviation for the word day, and then adds numbers to it. But he uses the normal numbers that you’d use to write about things like the commodities he’s recording – a trained scribe learns a particular specialised set of numerals that are only used when writing dates. There are other idiosyncrasies too – for instance he uses a falcon when he wants to write about Hori (because of the similarity of the name to Horus), and he has self-made signs for the commodities he’s recording mixed in with formal numerals. Again sometimes these are abbreviations of the words, e.g. for the various different types of bread, but they are not the abbreviations you’d use if you’d been properly taught the system. He also makes mistakes that a trained scribe would never do – sometimes he reverses signs, for instance.

Another interesting aspect of these documents is who is referred to with an identity mark and who is not. Any member of the crew is referred to by his own mark, but the men who bring the commodities from the temples do not. Instead their names are recorded using single hieratic signs for each section of the person’s name (Soliman showed us an example of a long name that was rendered as 3 single hieratic signs). Soliman said that this suggests to him that only full members of the crew had identity marks – it was an internal system associated with the core of the crew, not everyone who was connected with Deir el-Medina.

Soliman also compared the handwriting of these two sets of documents – to answer the question of whether it was one man in two contexts or two different men. After all one’s rushed notes in the moment are often a lot messier and full of personal shorthand than the report one uses them to write! He had answered this earlier – definitely two different men – but at this point he discussed some of the features of the documents that demonstrate this. The formal neat copies of the documents are written in a rather elegant hand with a sense of flair to the handwriting – this is someone who writes regularly and has developed his own style. The original documents show no signs of this, and the person who wrote them doesn’t seem to have a steady hand – this is something he does rarely and hasn’t had much practice with. The layout for the originals also gives away the lack of training of their writer – there isn’t an organisation scheme to it (no neat rows one after the other) instead it looks like he adds the entries wherever is convenient at the time.

Other documents look like a more direct collaboration between two scribes with differing levels of literacy. Soliman showed us an example (which is now in two halves, one in Berlin & one in Cairo) where it starts out being written by a trained scribe with an elegant hand – still using identity marks etc but with fluent hieratic notes. But then another hand takes over which is much less elegant and shows little sign of being trained in formal writing.

Another interesting document is one with a list of identity marks, each with a tally next to it for quantity of some unknown item. In the middle of this list is a woman’s name, and she is written out in hieratic rather than being identified with an identity mark. Soliman suggested that this might mean that women didn’t have identity marks in this system – backing up the idea that only full members of the crew had marks. However he returned to this in the Q&A and stressed that there’s a lot of nuance & uncertainty here. For instance sometimes the marks appear to apply a family, so in that case the women do have marks.

Soliman showed us a couple of ostraca that clearly demonstrate that the use of identity marks isn’t solely the province of the “literate to some extent” – one of these was a list of people alongside the products that they are bringing to a party or festival. The names are all identity marks while the commodities are listed in elegant (and correct) hieratic. There’s also an ostracon that juxtaposes ID marks and invented signs with text that shows all the hallmarks of true literacy. Surely a fully literate person would be able to write out people’s names properly, so why are they using ID marks? Soliman also noted that one of the ID marks on that ostracon is interesting in itself – it clearly derives from the word for the job of “vizier”, but obviously the man who is referred to with it is not a vizier! However he (and his father before him) is named after a vizier, so was this a little running joke within the community?

Another example of this trope of a literate person using textual features we are classifying as non-fully literate is an ostracon that Soliman referred to as a furniture ostracon. It has depictions of pieces of furniture, of types that we think are used in funerals. Alongside the pictures are notes in hieratic plus ID marks. Soliman said that these were probably made by a fully literate person, but intended to be used & “read” by a less literate worker. He thinks they are related to what Kara Cooney calls the informal workshop – where the goods for private tombs was built. So these furniture ostraca are translations of more formal hieratic documents into documents that are comprehensible to the craftsmen who are actually going to make this funerary furniture.

There are also a large group of ostraca with tally marks on, and sometimes drawings of objects. Some might be laundry lists – they have pictures of what look like the linen garments that have been found from the time period, along with counts of how many. But given they don’t have ID marks this opens up a lot of questions, and there was some discussion of this in the Q&A session. Perhaps people didn’t care which specific garment they got back so long as it was clean and the right sort? Or perhaps they aren’t laundry lists, and instead they are household inventories or list items for a funeral? But at least with these we do have some idea of a possible explanation – others are just lists of tally marks with no hint as to what was being counted or why!

Soliman finished his talk by drawing back from the details to consider the broader picture again. The big unanswered question is still what literacy actually is at Deir el-Medina, and there are a large number of the ostraca that had been found there that haven’t been properly studied. Work has focused on those with formal texts, and Soliman feels we need to look more at this unusually broad category of the workers who were “literate to some extent”. To do this we need to not narrowly focus on what we see as literate texts, but also look at the many different ways to make texts that don’t fall into our definition of literacy – with their pictorial representation, their invented signs and non-standard abbreviations. He said we should also broaden our notion of scribe (and this was returned to in the Q&A) – it’s not a protected title that you can only claim if you meet some criteria, so some people call themselves scribes when they aren’t really fully literate in our view. Literacy even to a limited extent was a status symbol and granted access to occupations and revenue sources, so a bit of self-taught ability to write was worth it. Soliman concluded that only after all of the evidence from the ostraca has been analysed (rather than just the “literate” texts) can we return to the question of what literacy is at Deir el-Medina.

I found this a really interesting talk. There is this tendency in the modern world to think of literacy as a binary – either you can read and write or you can’t – but even in recent history this wasn’t necessarily true. Soliman nicely illustrated how varied the spectrum of “literate to some extent” can be, and how at Deir el-Medina even partial literacy would be a useful skill.

Related Links

The texts that Daniel Soliman mentioned in his talk were:

- “Four Notes on Literacy” by John Baines & Christopher Eyre (which is available in “Visual and Written Culture”, a collection of articles & essays by John Baines)

- “From Single Sign to Pseudo-Script: An Ancient Egyptian System of Workmen’s Identity Marks” by Ben Haring

Other talks we’ve had at the EEG on related subjects:

- “Deir el-Medina: A Never Ending Story” Cédric Gobeil (an EEG study day in 2018, link goes to the first of four talks and there are links to continue at the end of each write up)