At the beginning of August Lee Young gave a talk via Zoom to the Essex Egyptology Group about the artist Lance Thackeray. Young is an independent researcher whose interests are primarily in the archaeological artists in Egypt, particularly the women. She said that most of the time she gives talks about people who have had a major contribution to Egyptology – this is debatable in the case of Lance Thackeray but he certainly made people laugh and be interested in Egypt! In this talk Young was covering three different aspects of her subject – Lance Thackeray the man, Lance Thackeray’s art (in particular from his book “The Light Side of Egypt”) and early tourism in Egypt which was the subject of Thackeray’s art. She began by sketching out the early life of Thackeray before moving on to include the other two subjects.

Lance Thackeray would need no introduction to postcard collectors as he created the designs for a lot of postcards – his humorous art on these cards gently satirised Edwardian society. But even so Young said that answering the question of “who was Lance Thackeray?” is quite difficult – he left no letters or documents, he never married and had no children so there was no-one to curate an archive of his papers, he died young in the First World War and even his publisher’s archive was lost to an incendiary bomb in the Second World War. But she said that some details of his life and personality can be pieced together from information in the public record and information in his books and postcards.

Thackeray was said to be very likeable and sociable, always smiling and he enjoyed life. But he was also always ready to slip away, a man on the edge of the party and a very private person. Young said that even in his popular work he eludes us – the humour in is work is immediately apparent, but he also makes us think and look at things differently. He was never cruel or unfriendly towards his subjects – even when poking fun at the ridiculous aspects of Edwardian life and society he was always smiling with his subjects rather than at them.

Although he was based in London for a lot of his career Lance Thackeray was not from the city. He was born in 1867 as the fourth of ten children in Darlington, County Durham. The name his parents gave him was Lot Thackeray – he would change this later. Young said Thackeray was fortunate to be born in an industrial town like Darlington where there was a School of Art that he could go to and be trained at. During his time there he was well regarded and won prizes, and was soon commissioned to illustrate books in pen & ink. This was also a good time to be an illustrator. The 1870 Education Act, which mandated schooling for all children, was leading to a rise in literacy and book publishing was taking off.

As a young man he moved to London for the opportunities it could bring him – both in terms of further training and in terms of a greater scope for a successful career. Originally he intended to continue his studies at a School of Art in South Kensington which was the parent institution of the School he’d attended in Darlington. But soon after he arrived he was making enough money as an illustrator to embark on a career. It was during this early time in London that he began to use the name Lance instead of Lot.

In 1897 Thackeray exhibited in London to critical acclaim, and he became a member of the Langham Sketching Club. Young said that in Edwardian society membership of a club was an important part of life – it was not just for the rich or upper class as we might assume these days. This club was held in high esteem at the time, but in 1898 some members including Lance Thackeray left to form their own club. This was not exclusively for painters and artists, but included other professions within the broader idea of the arts – those that were specifically excluded were “bumptious opinionated snobs”! By 1900 this new club, the London Sketch Club, was firmly established in the art world. The general public enjoyed their shows, as they were more fun than the conservative ones put on by other institutions.

But as the years went by Thackeray became detached from the club. Young said that the timing of their meetings was probably the explanation for this – they were held between October and May when most members were unable to paint outside and so they had time for the meetings. Thackeray on the other hand was spending those months in Egypt, painting and sketching commissions – this was the time of the year when he made his living. And so he eventually left the club he had helped to found.

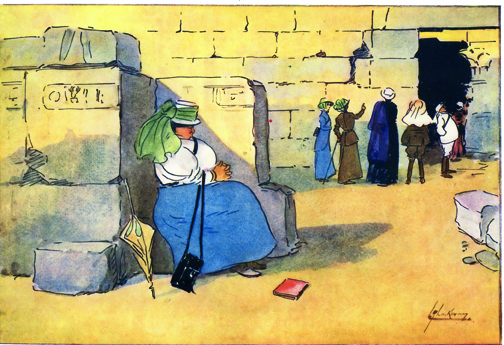

Young said that he was widely recognised as a skilled artist, with over 1000 designs for postcards many of which were based on Egyptian subjects. He also painted in watercolours, but his original paintings are now mostly lost. He was always sketching and painting, and would generously give his sketches away to people rather than storing them up in an archive, so not many originals are available now – his postcards are still available secondhand though. He made many watercolour sketches for his second book “The People of Egypt”, some of them in the field in Egypt. But this was difficult in the heat and conditions of Egypt so he also did pastel drawings which were easier to do while out and about.

Gradually Lance Thackeray became well known enough to exhibit on his own, rather than just as part of group exhibitions. This was particularly the case following the publication of his first book “The Light Side of Egypt” which was very successful. This book was published in October 1908, and 66 of the paintings were exhibited in that year as well. The book is a collection of light-hearted sketches with witty commentary – sharply observed but never cruel. The sketches focus on the people of Egypt, and the curious and sometimes ludicrous behaviour of the visitors.

Young now moved on to showing us images from Thackeray’s book (and reading us some of his commentary), juxtaposed with photos and information about the rise of popular tourism in Egypt during the late 19th and early 20th Century. She told us that she’d missed out a couple of Thackeray’s sketches as they were simply too non-PC these days, and warned us that his descriptions do reflect the attitudes of the time (as you’d expect).

The sketch that Young showed us first was of a scene that might still feel familiar today (as many were, actually) – it was titled “The Vultures” and showed a tourist emerging from his hotel (Shepheard’s Hotel) in Cairo, and surrounding him are Egyptian dragomans jockeying for his attention. The description Young read out was a witty description of these vultures including lines like “his favourite hobby is asking for baksheesh”, and commentary on how the dragoman will receive a kickback from anyone the tourist buys goods from whilst in his company.

(I had to look it up – according to wikipedia “dragoman” (plural: dragomans) is a word for translators and official guides in Middle Eastern countries derived originally from the Semitic language family (including ancient tongues such as Akkadian) and passed into European languages as a loan word, but in this case I think it’s being used more broadly to mean what we would refer to as a guide as well as the taxi drivers, caleche or boat operators etc etc. Essentially the Egyptians who make their money from tourism and the tourists.)

Shepheard’s Hotel, the scene of that sketch and the next one, was “the” hotel in Cairo. It was the epitome of glamour – Young read a quote that said that “it was not the people who lent atmosphere to Shepheard’s but Shepheard’s that lent atmosphere to them”, and the cliche was that if you sat on the terrace long enough you’d see the world walk by. And as the next sketch that Young showed us illustrated – you’d also see a lot of Egyptians providing entertainment, and selling tourist tat to the Westerners sat on the balcony.

Tourism as we know it only started in the mid-19th Century. The earliest proper guide book to Egypt was published in 1840 (by which Young meant one that wasn’t just an account of someone’s journey but was written with the intent to help the reader plan and undertake their own trip), with another couple published in the next few decades. Visitors generally landed at Alexandria, then hastened by boat of train to Cairo. There they would stay a few days, or perhaps a month or two, before setting off up the Nile.

Travel in Egypt has, of course, always involved the Nile, and boats were always important to the Ancient Egyptians. And to the modern Egyptian, and tourist. The dahabeya was the boat of choice for early Western travellers. The name comes from the Arabic word for “golden” – referring to older really quite luxurious boats, but by the 19th Century they were much more modest than that!

The first task for any would-be traveller therefore was selecting a boat – which sounds rather easier said than done. Young said that Amelia Edwards talked of being faced with two or three hundred possible boats to choose between, and Gardiner (I think that’s who Young said) suggested that the first thing to do with a boat was to sink it to get rid of the rats!! The well heeled travellers who were the original tourists would, after they’d chosen their boat, have their own personal flag flown so that friends and acquaintances could recognise them as they travelled.

Young showed us a photograph of Thomas Cook’s inaugural tour – these tourists had been greeted by Cook himself at London Bridge, and he had escorted them across Europe to the Mediterranean and thence to Alexandria. From there they did hasten to Cairo, where they only spent a couple of days before boarding their boats to go up the Nile. This was a new sort of trip which opened up travel in Egypt to classes of people who previously couldn’t’ve afforded it. In addition Cook promoted himself as “the travelling chaperone”, and his excursions and tours appealed to women in particular as they felt safe travelling “on their own” whilst on one of his trips. Not everyone saw this as a good thing, Young told us that hostile commentators referred to “Cook’s Hordes” or called his tourists mental patients!

The next sketch that Young showed us was of tourists near the Sphinx, called “Visit to the Pyramids” – Thackeray’s description talked about the tourist trying to get into the romantic spirit with camel or donkey rides and contemplation of the Sphinx. Only to get dragged back to reality by a reminder of his lunch engagement, and the perennial requests for baksheesh. Another of the sketches was of a tourist having his photograph taken on a camel with the Pyramids in the background – another one still with relevance today, although as Young pointed out camera technology has changed a lot since then. Thackeray’s commentary on this one talked about how the photograph would end up on the wall in the tourists home to impress visitors’ with how well travelled he was.

Continuing on the theme of both Pyramids and living up to or surpassing the expectations of one’s friends at home was a really funny sketch of tourists climbing the pyramids with a lot of help from the Egyptian dragomans. Thackeray’s commentary refers to it as an obstacle race, and notes that everyone expects it of you – the first question when you return home will be if you climbed the pyramids or not. And thus even those who don’t exert themselves at all at home will go up the pyramid at least far enough to satisfy the expectation (with much help, and much baksheesh to the helpers).

Young next showed us Thackeray’s sketch titled “Cup and Ball (The Camel’s Favourite Game)”. This was of tourists bouncing uncomfortably on the top of camels as they picked up speed – his commentary talked about how you needed to try to land the ball (yourself) in the cup (the gap between the humps) else it’ll hurt!

The next series of sketches were of the sorts of events that could take place while cruising along the Nile. Young commented that Cook’s itinerary for the Cairo to Luxor cruise leg was still followed into the 1980s (when sadly security concerns meant no tourists were permitted in Middle Egypt). These sketches included “Sun Worshippers”, with all the tourists lined up at the boat railing to watch the sun rise or set on the first day but after the first few days interest would trail off.

Another of these sketches was “The Battle of the Nile” which riffed off a famous painting (embarrassingly I didn’t manage to note down which one) – it shows a tourist between two or three Egyptian dragomans pulling him in opposite directions to come to their donkey which was, of course, the best very good donkey. Thackeray’s commentary said that the experience was “survivable with the help of the police” who would beat only the Egyptians with their sticks, but never a tourist. Young also showed us one called “Fed Up” of a tourist hiding in the shade at a temple rather than join the tour – Thackeray’s comment was “there were those whose physique was never meant to undergo such strain”.

Fed Up, Lance Thackeray

The first of Cook’s tours coincided with the second trip of Prince Albert (the Prince of Wales) to Egypt – Queen Victoria having sent him off purportedly on a second honeymoon with his wife. The timing was convenient to avoid the growing scandal of his adulterous affair with a prominent member of society (and the first visit had coincided with a scandal centred on a prostitute – Victoria was clearly a believer in “out of sight means out of mind”). The royal party travelled in lavish style – Young showed a photograph of the salon on the royal barge where the party would sing accompanied by piano & bagpipes!

The coincidence of the tours caused great excitement among Cook’s passengers, but was rather less well received on the royal side. Young read out the opinion of one the party, which commented at length on his distaste for having a multitude of English turn up at the sites just as they themselves did, and even worse they were “people no-one knew”. Which explains it all – Cook was aiming to democratise Nile tourism, and this did not go down well with the more snobbish members of Edwardian society! And Young again stressed that while Thackeray was poking fun at these tourists, it wasn’t that sort of mean snobbishness.

The next couple of sketches (“Bargain Hunting” and “The Antique Pest”) were about the lengths to which the Egyptian locals will go to sell things to the tourists. No matter where the tourist alights from the boat there will shortly be someone ready to sell them a bargain, and to haggle over the prices. A familiar feeling today, as is the antique pest in slightly different form – in Thackeray’s sketch this was a man described as producing from a dirty bag in his dirty robe a “genuine” antique which he will then walk for miles attempting to sell to the tourist, who eventually pays up just to be rid of the seller! These days it’s just a little different, because it’s illegal to sell genuine antiquities the sellers are more honest about it being their own work. But just as persistent in my experience! Another familiar experience is people watching while cruising on the Nile, which Thackeray’s sketch “Nile Skyline” depicts.

Donkeys and the difficulties they can get you into were the subject of a couple of the sketches – “Ouah! Riglak!” depicted the upset caused when one’s donkey walks straight into locals who either hadn’t heard one approach or hadn’t felt it necessary to move. The description that Young read out of this focused on the “language learning” opportunities, as you’d hear Arabic words you otherwise wouldn’t. I was particularly amused by the start of this quote, where Thackeray talks about the first & last word one hears is “baksheesh” and the first word one learns is “imshi!”.

The next two sketches Young showed us depicted particular sub-types of tourist – “Beauty and the Beast” is about the sort of pretty young lady who occasionally shows up on tours (arriving with mother, of course) and gathers all the male attention for herself, changing the mood of the tour. And in contrast was the woman of substance – described by Thackeray as “someone’s mother-in-law, no doubt” who needs help perching on the donkeys and getting about the sites, and ends up with a much lighter purse.

And the last of the sketches that Young showed us from “The Light Side of Egypt” was appropriately titled “The Parting Guest”. Thackeray’s accompanying description talked about how any attention that’s been lacking on the holiday is more than made up for on your day of departure as all the staff appear to see you off (and ask for baksheesh, of course!).

Having given us a fascinating look at the sketches from “The Light Side of Egypt” Young now moved on to finishing off the other two threads of her narrative. First she outlined for us the later fortunes of Thomas Cook’s tours. Cook, and later his son John, expanded their tours and were of course joined in Egypt by companies from other countries. They established a steamer service in the 1850s (of course snobbishness meant that the independent traveller still went by dahabeya). At first the furthest south the steamers went was Aswan, as they couldn’t get past the cataract. But Cook subsequently brought in a smaller steamer that could be manhandled past the cataract like a dahabeya which let him run tours down to Abu Simbel – Young illustrated this with a striking photo of the temple in its original context on the very edge of the Nile.

Tourism was good for the ordinary Egyptians – bringing money into the country which went directly to them. Those who benefited ranged from those who sold food to the tour boats through to those who brought donkeys for the tourists to ride on. Young told us that during an armed uprising with anti-European sentiment in 1882 none of Thomas Cook’s property was damaged because they weren’t regarded as part of the problem. Of course, this wasn’t actually true – for instance Cook’s boats were used to transport British troops that came to quell the disorder.

That episode left Cook’s boats in disarray, having been poorly treated whilst being used as troop carriers. So they were replaced with a new fleet to accommodate the returning tourists. As tourism continued to increased, so did the number of boats in Cook’s fleet. The last first class steamer to be added to the fleet was “The Sudan” which is still operational – and was used in the filming of Death on the Nile (and you can visit the steamer today and see all the rooms used in the film).

Young now finished by talking about Lance Thackeray’s further life and career – which was sadly rather short. His second book “The People of Egypt” was published in 1910, and was described as a “delightful record of the people of Egypt as seen through the eyes of the artist”. It consists of paintings of the styles of dress and occupations of the Egyptians, and has no descriptive text by Thackeray (which I felt was rather a shame, I’d greatly enjoyed the excerpts that Young read out to us!). In this book you see his style beginning to evolve – this were not cartoon-y sketches but were in a more painterly style. And Young said that his work beings to show signs of the influence of Expressionism – and more intent on conveying an emotional reaction than just a humorous sketch.

Sadly we never got to see how his work would’ve matured further. His health was declining – he’d had colitis in Egypt and he was generally getting weaker even as World War One made travel in Egypt less practical and less pleasant. By 1914 life was changing for artists, as well – the fashion for buying and collecting postcards was declining so there was less need for artists like Thackeray to produce designs for them. The great years of postcards were over – and some of the artists volunteered for the army, others took on propaganda work.

Lance Thackeray, despite his ill health, volunteered for the Artist’s Rifles. He didn’t in the end ever serve in the war itself – he underwent training, and due to his skill as a draftsman was promoted and sent for officer training. Even during this time he was sketching all the time (and giving his sketches away) – and he was generally popular with his comrades. But his military service proved disastrous – by 1916 he was seriously ill with both colitis and pernicious anaemia. He collapsed, spent three days in hospital and a few weeks later was discharged from the army as medically unfit. He died the day after, at only 49 years old. His grave is in the Lewis Road extension cemetery in Brighton, but is sadly neglected.

I enjoyed this talk – a little bit of light relief, and while I hadn’t been aware of Thackeray’s work before I’ll be keeping an eye out for his sketches in future.