The temple at Medinet Habu is one of the best preserved temples in Egypt. It was Ramesses III’s memorial temple, known in Ancient Egypt as the Mansion of Millions of Years of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt User-Ma’at-Ra-Mery-Amun in the Estate of Amun on the West of Thebes. And typing out a name like that always makes me wonder if it was significantly shorter in Ancient Egyptian or if they had shorter names to refer to the temples by! The design of this temple is quite similar to the other mortuary temples we visited earlier in the trip – those of Seti I and Ramesses II. Possibly a standard design, although Kent Weeks in his Luxor guidebook ascribes it to being another instance of Ramesses III emulating Ramesses II (along with naming his sons the same things as Ramesses II named his and so on).

My photos from this site are, as always, on flickr and you can click here for the full set or on any photo to go to it on flickr.

We started our visit with a bit of explanation from Medhat about the temple, mostly concentrating on the harem and the entrance to the temple. The gate that leads into the temple enclosure is much more like a fortification than one would expect for a religious site. This might be a case of literalising a metaphorical concept of the enclosure wall protecting the sacred space from profane contamination, or it might be that the unsettled political and economic climate of Ramesses III’s time necessitated protection. This is the time of the Sea Peoples, a mass migration of people across the Mediterranean that caused disruption in several of the more settled countries in North Africa and the Middle East. It was also a time of domestic problems – including possibly a successful assassination of Ramesses III himself. (There was a paper three years ago about this which I wrote about at the time, where they claimed to’ve identified the fatal wound and the killer’s mummy.) The fortified gate includes windows at a high level which had stone heads along the window sills. Medhat told us that these, like the design of the gate, are based on Assyrian structures. But executed in a typical Egyptian fashion – where the Assyrians used real human heads cut off their enemies, the Egyptians made stone ones so that their enemies were symbolically mutilated and displayed for eternity.

After this we were let loose to explore ourselves. John and I started by having a brief look at the palace to the southwest of the temple proper. The walls of this have been partially restored so you do get a sense of the shapes of the rooms (although not of how it would’ve looked – as it’s difficult to imagine how the ruined half-walls looked when decorated and lived within). These included an audience chamber where Ramesses III would’ve held court. And it even has an en-suite toilet in a small chamber on one side, all mod cons!

After looking at the palace we moved back to look more at the temple itself. As well as looking at the front of the temple and the outside walls we spent a lot of time in the First and Second Courts. The outside of the First Pylon has the traditional scenes of the Pharaoh smiting his enemies, and the military theme is continued within the First Court which was not only part of the temple but also the forecourt for the palace. Around the walls of the court are scenes of defeated enemies, and the penises and hands of dead enemies (not attached). Unlike Ramesses II who had his one battle that he liked to depict everywhere (Kadesh), Ramesses III had several campaigns he wanted represented. These included fighting against the Sea Peoples who attempted to invade during his eighth regnal year, and a campaign in Syria against an Amorite settlement.

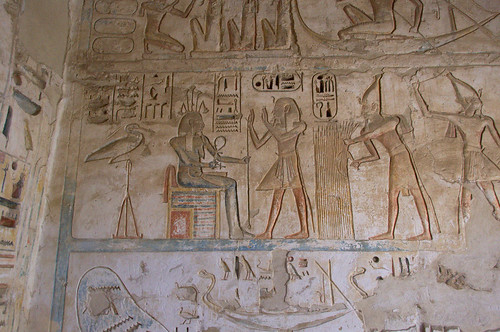

One thing that’s really noticeable about the reliefs in this temple compared to other sites we visited is the depth of some of the heiroglyphs. They vary from very shallow sunk relief to very deep indeed – so deep that pigeons can sit in the holes. I find this fascinating – the different depths are jumbled together and I feel like there must’ve been some scheme or rationale behind the differences. But I don’t think anyone knows the reasons – I did ask both Dylan and Medhat and they didn’t know.

The Second Court reliefs still retain a lot of their original colour – particularly under the colonnade. We spent a lot of time in here just admiring them and photographing them. I also found some graffiti – there is always graffiti, this stuff was mostly early 19th Century. Once through this court the temple is suddenly roofless. It feels like someone came along and sliced the top off with a (very large) knife. The Kent Weeks Luxor book says that the stone was removed by later builders using the temple as a quarry, as so often happens when a building falls into disuse over the centuries. The temple guardians in this section were fairly predatory and had closed off some of the side chapels with fences in the hope they could con us tourists into handing over extra money to see things that should’ve been freely accessible. One of the other people in our group (the other Margaret) managed to talk one of them into changing his tune by saying she’d report them to the Ministry, and so we did get to go into a chapel we would otherwise have missed out on. It had some interesting scenes in it of the Pharaoh reaping corn and ploughing fields – I don’t think I’ve seen reliefs like that before in a temple.

Medinet Habu is a huge temple and has loads of well preserved things to see, so we didn’t have nearly enough time here. But we’d’ve had to miss out other things to get more time and I don’t think I could pick one to do without!