The ancient Egyptian village at Deir el Medina was the home of the people who worked on the tombs of the Pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings. The families who lived there were relatively high status (for common people) as they were skilled craftsmen. They were also kept isolated from the general population because they knew where tombs were and the materials they worked with were also valuable. The village also had a high literacy level, and so a lot is known about their lives from the discarded ostraca (bits & pieces of pottery & limestone) that they used to write notes.

My photos from this site are up on flickr, as always, click here for the full set, and on any photo in the post for the larger version on flickr. Flickr have changed the way their embed links work in a way that breaks my layout for small photos so I’ve fewer (but larger) pictures in this post and have linked a few from the text to illustrate specific things.

We started our visit by the side of the village proper. It’s actually pretty difficult to a get a feel for it from ground level – all that’s visible are the remains of the walls and it just looks like a confusing maze. Striking in an abstract visual sense, but not very informative. I think the photos J took from the mountain the day before we visited (like this one) give more of a sense of the layout. We didn’t spend much time looking at the village itself tho, which was a bit of a shame – but I’m not sure you’re ever allowed to go wandering in among the walls.

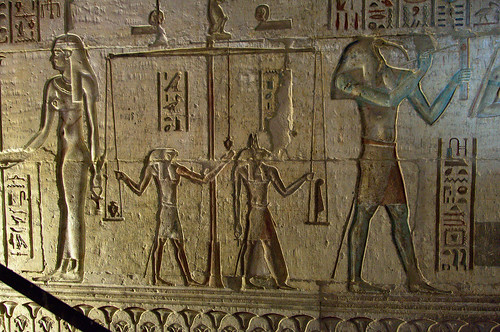

At the far end of the site from where we started is a temple. It’s enclosed within a mudbrick wall, as are the remains of other smaller buildings. The temple is a Ptolemaic era replacement of the New Kingdom temple(s) on this site. The whole site was subsequently used as a Christian monastery, and so there’s a lot of Coptic graffiti on the walls of the temple. Inside the decoration still has a lot of colour and some unusual scenes for a temple. In one of the chapels is a relief showing a weighing of the heart scene, familiar from Book of the Dead papyri and tombs but rare in temples. There are also two columns with representations of historical personages who were later deified. One of these is Imhotep, the architect of the Step Pyramid some two & a half thousand years before this temple was built. The other was Amenhotep, son of Hapu, who may’ve built an earlier temple on this site during the New Kingdom period.

After we’d looked around the temple we came out of its enclosure and went round to the north away from the village to look at the Great Pit. This was originally dug to be a well, during the 18th Dynasty (I think), but they never reached the water table. It’s enormous – the Kent Weeks book gives the dimensions as 50m deep and 30m in diameter, which seems implausibly large for a well (in width). Even tho it’s not clear why it was built like this, it is clear that once they failed to find water the only use for the pit was as a rubbish dump. From this were excavated large numbers of pottery shards and limestone fragments originally used for writing notes. These have provided archaeologists with a fascinating insight into the daily lives and concerns of this group of high status craftspeople. There’s nothing to actually see here, except a chance to boggle at the size of the pit. I still found it fascinating.

We finished our visit to Deir el Medina by looking at two tombs of craftsmen who had lived here. As one would expect these are decorated with high quality art – this was after all the village where the best artists lived. Two tombs are open to visitors, one belonging to Inerkha and one to Sennedjem. They were very small and the passages leading down into them were twisty and steep. The scene that particularly caught my eye in Inerkha’s tomb was of a cat cutting off a snake’s head with a knife. There was a scene like that in Sennedjem’s tomb as well, but the striking one here was an image of Hathor in a sycamore tree where the tree’s trunk ended in a giant foot!